LIVING IN HARMONY

Project for two timber-framed residential buildings

Late 1950s. When they rose up opposite the Vernier cemetery, the buildings designed by architects François Maurice, Jean Duret and Jean-Pierre Dom brought an unusual modernity to the landscape. At the time, the municipality had not yet undertaken the creation of the large satellite towns of Lignon, Libellules and Avanchets, which were necessary to absorb the population growth of the second half of the 20th century. And in this loop formed by the Rhône riverbed, at least, Vernier remained fairly rural.

Comprising a total of six low-rise buildings forming two offset ‘T’ shapes, this affordable housing complex offers simple, rational architecture that has been well preserved until now. The neighbourhood is quiet, the flats are pleasant and the rents are modest. But after three generations and despite constant maintenance, the buildings are showing clear signs of wear and tear. The initial idea was to renovate the entire complex and bring it up to current standards. But the key issue lies elsewhere, as the potential for densification of this largely open area appears to be very interesting and the opportunity for an advantageous change of zoning seems to be on the horizon.

All options are then on the table: the possibility of raising the existing volumes, demolishing everything and rebuilding from scratch, or renovating the existing structure as little as possible and then filling in the exterior surfaces with new constructions. These are all reliable options that have proven their worth, but new considerations have been added, raising a legitimate question: what are the most appropriate criteria today for intervening in a built-up area with a view to increasing the land use index? The answers are to be found, of course, in economic factors, but also in sustainable development, heritage issues, social realities and expertise in urban transformation. These are different and perhaps contradictory problems, but they must be combined to provide an intelligent response that is tailored to the specific characteristics of the site and the needs of those who will live there.

The survey conducted among the population directly affected – the buildings are inhabited – shows a strong attachment to the neighbourhood and, in fact, argues for the preservation of these buildings, which are obsolete in many respects but still perfectly functional. This position is at odds with the view of architect François Maurice himself, who, nearly 70 years after designing this housing project, maintains that complete demolition is still the best solution. As for the buildings themselves, upon closer inspection, they reveal problems that are ultimately fixable and no major design flaws, whether in terms of construction or typology. The only widely recognised weakness of the complex is the rather poor management of the outdoor facilities, which, in keeping with the era in which they were built, give priority to cars. This informed assessment allows us to consider all the parameters and rule out options that are too costly, too intrusive or too energy-intensive. The time has now come to design a project that respects the scale of the site and its population.

Despite François Maurice's opinion (but also in homage to his architecture), the initial idea was to fully preserve the six existing small buildings. Structurally too fragile to be raised, these buildings are being given a new lease of life that combines the preservation of their expressive and material qualities with improved thermal performance and general upgrading to current standards. This is a simple and effective choice that also allows work to be carried out while the site remains occupied, without evicting anyone, with tenants moving around as the flats are converted one after the other.

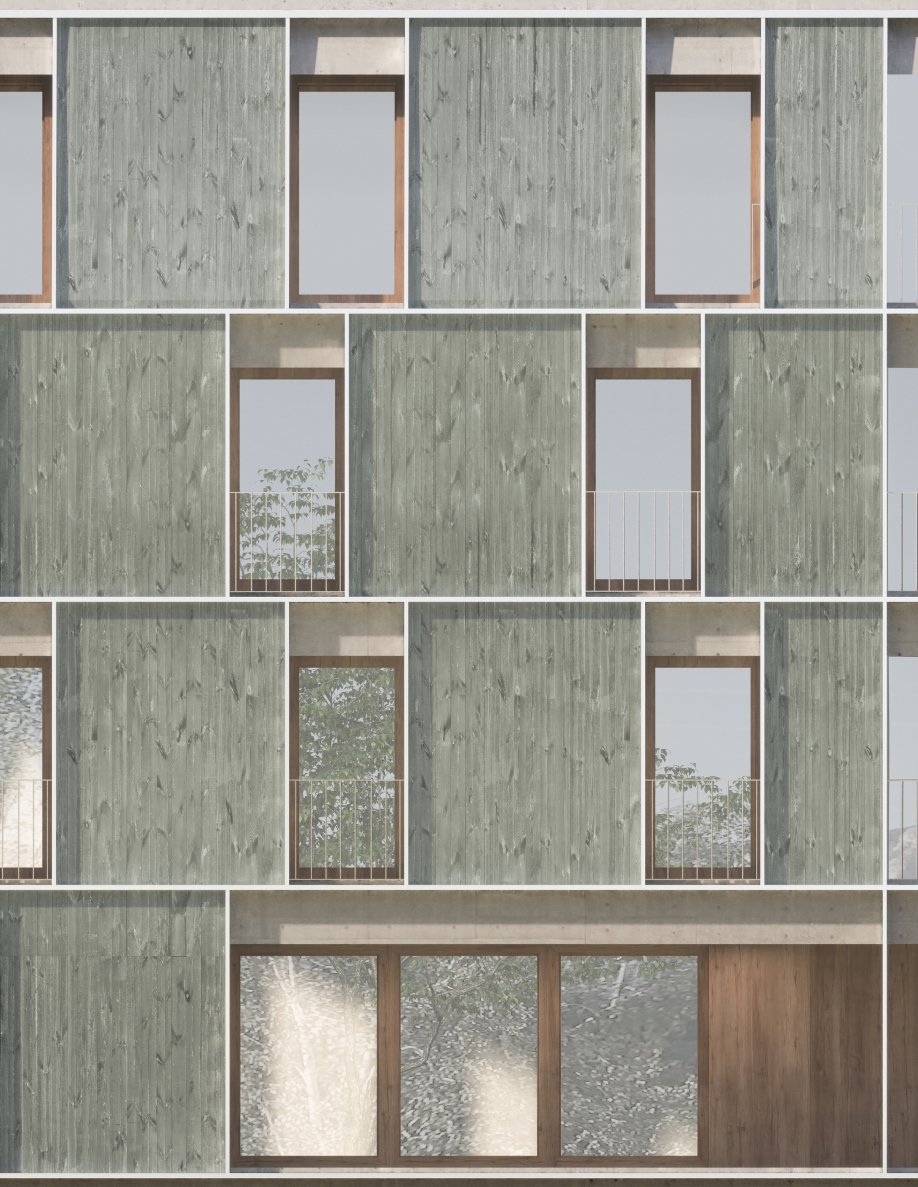

At the same time, this transformation/renovation project is being carried out in conjunction with the construction of two new buildings, located in the centre of the development, between the two largest wings formed by the existing 1950s buildings. These two planned structures are essential elements of the overall project and are located in the largest open space on the site. Irregular, elongated pentagons, they interact with each other and with the surrounding built environment, contributing, without seeking to mimic it, to the redevelopment of outdoor areas that have been virtually abandoned for decades. Designed with a wooden envelope and frame built around a concrete core dedicated to common areas, these buildings house a large number of three-, four- and five-room apartments, all with multiple orientations, under a four-storey structure with a flat roof. The aim is to achieve THPE (very high energy performance) certification thanks, among other things, to the installation of solar panels in the buildings, capable of providing heating throughout the cold season using energy produced and stored during the summer. Outside, the landscaping has been redesigned and parking spaces have been removed, replaced by a spacious underground car park, which is also entirely new.

Presented to the authorities and local communities, this project, which has been meticulously developed over nearly ten years, has been very well received. Supported by people who are directly affected or very familiar with the needs, the shared enthusiasm bodes well for its imminent implementation. Unfortunately, this does not take into account the political calendar and the vagaries of municipal and cantonal spatial planning. Contrary to all expectations, the framework conditions that made such a project possible have been overturned and are now shelved. Caught up in the quagmire of administrative practices and governance strategies, the restoration of a piece of Geneva's architectural heritage, coupled with the construction of more than thirty new homes, will not go ahead. For how long?